You

Write a 1,000 word blog post for the Guerrilla Cartography website on how AI is changing cartography.

ChatGPT

Title: The Cartographic Revolution: How AI is Transforming Maps

In the ever-evolving landscape of cartography, a silent revolution is underway. It’s a revolution powered by artificial intelligence (AI), reshaping how we perceive, create, and utilize maps. Gone are the days of manual charting and static representations. Today, AI is at the forefront, driving unprecedented advancements in mapping technology. From automated feature extraction to real-time updates, personalized navigation, and environmental monitoring, the impact of AI on cartography is profound and far-reaching.

The Rise of Automated Mapping

At the heart of AI’s influence on cartography lies its ability to automate previously labor-intensive processes. Imagine a world where maps are no longer painstakingly hand-drawn but instead crafted with precision and efficiency through AI algorithms.

Feature Extraction:

AI algorithms can now scan satellite imagery with remarkable accuracy, identifying and extracting features such as roads, buildings, rivers, and more. This means that what used to take weeks of manual tracing can now be accomplished in a fraction of the time, allowing cartographers to focus on higher-level analysis and interpretation.

Land Use and Cover Mapping:

One of the most impactful applications of AI in cartography is in land use and cover mapping. By analyzing satellite data, AI can classify different types of land cover, from forests to urban areas, with impressive detail. This not only provides valuable insights into our changing landscapes but also helps in urban planning, agriculture, and environmental conservation efforts.

Accuracy Redefined

AI not only accelerates mapping processes but also enhances the accuracy and reliability of the resulting maps.

Quality Control:

With AI’s keen eye for detail, errors in maps can be quickly identified and rectified. Inconsistencies in data, such as mismatched road networks or misplaced landmarks, can be automatically flagged, ensuring that maps are as precise as possible.

Data Fusion:

By seamlessly integrating data from multiple sources—satellite imagery, GPS, aerial photos—AI produces maps that are more comprehensive and up-to-date. This fusion of data leads to richer and more detailed representations of our world.

Real-Time Updates and Dynamic Maps

The days of static, outdated maps are behind us. AI enables the creation of dynamic maps that reflect the ever-changing nature of our environments.

Real-Time Monitoring:

Whether it’s monitoring traffic conditions, tracking weather patterns, or responding to natural disasters, AI-powered maps provide real-time information crucial for decision-making. Emergency responders can rely on these dynamic maps to navigate evolving situations with precision and speed.

Crowdsourced Data Integration:

AI is also adept at processing and integrating crowdsourced data from platforms like OpenStreetMap. This means that community-contributed updates, such as new roads or points of interest, can quickly find their way onto official maps, ensuring that they are always current and relevant.

Personalized Mapping Experiences

AI doesn’t just stop at creating maps—it’s also revolutionizing how we interact with them on a personal level.

User Behavior Analysis:

By analyzing user preferences and behaviors, AI can tailor maps to individual needs. Whether it’s suggesting optimal routes based on past travel patterns or highlighting points of interest aligned with a user’s interests, maps become more than just navigation tools—they become personalized guides.

Contextual Mapping:

Maps can now adapt to the context in which they are used. Factors such as time of day, weather conditions, or nearby events can influence how a map is displayed. For example, a map might highlight nearby cafes in the morning and restaurants in the evening, providing a seamless and intuitive user experience.

Visualizing the Future

The visual appeal of maps is also undergoing a transformation, thanks to AI.

Style Transfer:

AI can apply different styles to maps, allowing users to choose between classic, watercolor, or even futuristic renditions. This not only adds a layer of aesthetic appeal but also serves practical purposes, such as optimizing maps for specific audiences or purposes.

3D Mapping:

With AI, we are witnessing the rise of detailed 3D maps that offer a new perspective on our world. Whether it’s visualizing urban landscapes or exploring natural terrain, 3D maps provide a richer and more immersive experience.

AI for Environmental Monitoring

The power of AI extends beyond just human landscapes—it’s also making a significant impact on environmental mapping.

Change Detection:

By comparing satellite images over time, AI can detect changes in vegetation, water bodies, and urban areas. This capability is invaluable for environmental monitoring and conservation efforts, allowing us to track deforestation, monitor wildlife habitats, and respond to ecosystem changes.

Habitat Mapping:

AI’s ability to analyze satellite imagery is instrumental in mapping habitats for various species. Conservationists and researchers can use these maps to identify critical areas for protection and better understand the interconnectedness of ecosystems.

Navigating the Future with AI

The influence of AI on cartography is undeniable, but it also presents challenges and considerations.

Data Privacy:

As AI relies heavily on data, concerns around privacy and data security are paramount. Safeguarding personal location information and ensuring transparent data usage practices are essential.

Algorithm Bias:

AI algorithms are not immune to biases present in the data they are trained on. This can lead to inaccuracies or unfair representations in maps, highlighting the importance of diversity and inclusivity in data sources.

Technical Challenges:

The processing of vast amounts of geospatial data requires powerful computing resources and efficient algorithms. Continued advancements in AI technology will be crucial to overcoming these technical hurdles.

Embracing the Cartographic Revolution

In conclusion, we are witnessing a cartographic revolution driven by AI—a revolution that is reshaping how we map and navigate our world. From automated mapping processes and enhanced accuracy to real-time updates, personalized experiences, and environmental monitoring, the possibilities are endless.

As we continue to harness the power of AI in cartography, it’s essential to remain vigilant about data privacy, algorithmic biases, and technical challenges. By addressing these concerns, we can fully embrace the potential of AI to create maps that are not just informative tools but also works of art that inspire, educate, and empower us to explore the world around us.

The future of cartography is here, and it’s powered by AI. Let’s embark on this journey together, charting new territories and discovering the boundless possibilities that lie ahead.

You

Add three examples or images that illustrate the main points of this blog post

ChatGPT

Certainly! Here are three examples or images that illustrate the main points of the blog post on how AI is changing cartography:

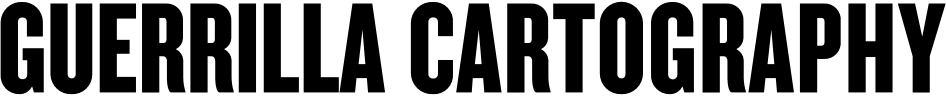

1. Feature Extraction: Before and After AI

Image Description: A comparison between manually identifying features in a satellite image (left) versus AI-automated feature extraction (right). The AI-automated process shows clearly identified roads, buildings, and water bodies with labels.

Caption: AI-powered feature extraction drastically reduces the time and effort required to identify and map features such as roads, buildings, and water bodies. The image on the right demonstrates the efficiency and precision of AI in extracting these features from satellite imagery.

2. Real-Time Updates: Dynamic Traffic Monitoring

Image Description: A dynamic map displaying real-time traffic conditions with color-coded lines indicating congestion levels on roads.

Caption: Real-time updates powered by AI enable dynamic maps like this one, which shows live traffic conditions. Color-coded lines represent varying levels of congestion, providing users with up-to-the-minute information to plan their routes efficiently.

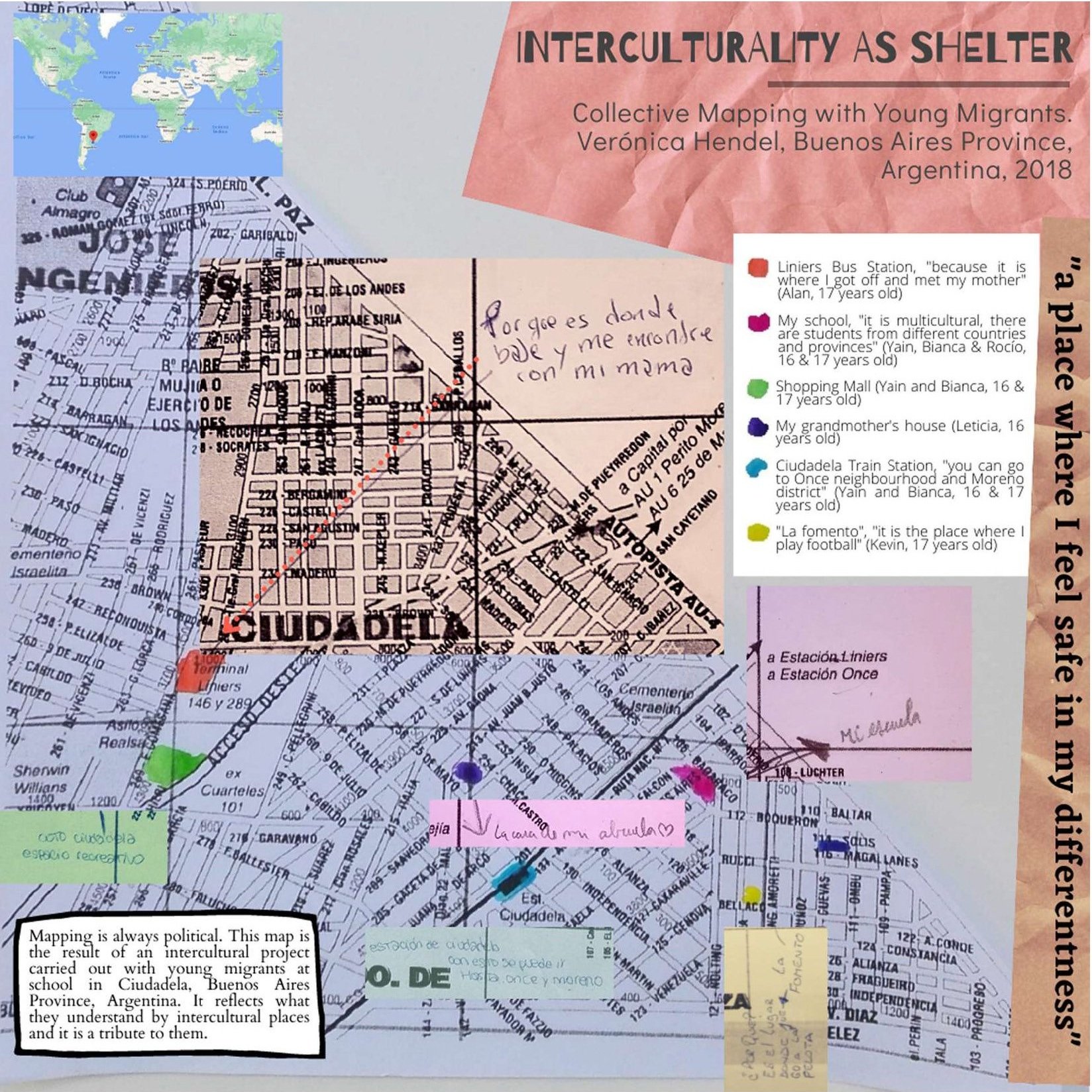

3. Personalized Mapping: User Behavior Analysis

Image Description: A personalized map displaying suggested points of interest based on the user’s preferences and past travel patterns.

Caption: AI analyzes user behavior and preferences to create personalized maps. In this example, the map suggests points of interest based on the user’s past travel patterns, enhancing the user’s experience by providing relevant and tailored information.

These visual examples complement the main points of the blog post, showcasing how AI is transforming cartography through feature extraction, real-time updates, and personalized mapping experiences.